Reminder: find my roundup of the latest transport decarbonization news at the bottom of this email.

Carbon Free Boston

I’ve been pushing for more cities to put forward transport decarbonization plans, grounded in real data, outlining what it would take to get to a zero carbon world. A few weeks ago, we looked at TransformTO, Toronto’s plan to do just that. Today, we turn to Boston.

Carbon Free Boston, published in 2019, outlines a path for the city to hit net zero emissions by 2050. So what’s in it?

First, Buildings

The first thing to note is that while transportation is the largest source of emissions in the United States and Massachusetts, it’s far from the City of Boston’s biggest emitter. Almost two-thirds of Boston’s emissions come from buildings. That’s all the energy we pour into heating them, cooling them, lighting them, etc.

New York also produces about two thirds of its emissions from buildings. That makes sense. One of the advantages of cities is that you can get what you need while traveling shorter distances, and you’re more likely to be able to walk, bike, or take transit where you go, consuming less energy per mile travelled. Cities have already done a lot to ‘solve’ the transport decarbonization problem, so it’s not uncommon for their biggest emitter to be buildings. You can use it as a handy test of how urban or suburban the area you live in is: is your biggest source of emissions buildings or transportation?

What to do about transportation?

The bulk of the remaining emissions (29%) in Boston come from transportation. The authors recommend three actions to bring these to zero: (1) getting people out of their cars, (2) electrifying the cars that are left, and (3) ensuring that electric power is renewable. That’s actually a pretty good summary of any urban transport decarbonization plan. The devil is in the details.

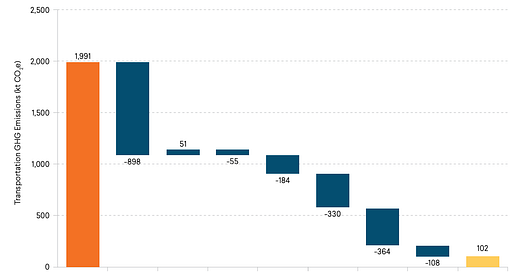

The diagram below shows the relative importance of every policy the authors propose. Total 2016 transport emissions are on the left. The first blue bar, labeled “Growth and Vehicle Efficiency”, drops emissions about 40% from 2016 levels. This represents the baseline reduction the authors expect by 2050 without any additional action, mostly as a result of federal fuel economy standards that have since been rolled back by the Trump administration (uh oh). We’ll go through the next actions in sequence, below.

Getting People Out of Cars

The next set of actions - labelled, in order, ‘unmanaged smart mobility’, ‘transit focused growth’, and ‘pricing’, all fall under the umbrella of getting people out of their cars.

The first bar - 'unmanaged smart mobility’ - is the report’s shorthand for describing the increase in vehicle miles travelled (VMT) the authors ascribe to the rise of ‘shared mobility’ services like Uber, Lyft, microtransit, and potentially autonomous vehicles. There’s actually a pretty interesting deep dive on the potential emissions increase or decrease from these services in the technical report (starting on page 68) that I won’t get into here, but hope to cover in a future newsletter. Overall, they estimate an increase in emissions as a result of the significant growth of these services.

The next bar - ‘transit focused growth’ covers both big increases in transit service and more focused urban development efforts around transit hubs. There’s a lot in that little bar, including 35 miles of new urban rail (!), 42 miles of rapid bus lines, free or discounted transit fares, and 250 miles of new protected bike lane. It’s hard to think of a US city that has completed anything like that program of investment in recent years.

The result is that daily transit ridership increases from 470,680 trips in the baseline to 672,406 in the low carbon scenario, a 43% increase. And yet, despite that growth, the reduction in emissions is modest - only about 2.7% from baseline. Bike investments reduce VMT by just 0.5%. (If you have a strong reaction to those results and want to dive deeper, you can find more detail on page 56-63 of the technical appendix.)

I’ll pause here to make an important note: transit, walking and biking investments provide important benefits that go well beyond decarbonization, increasing access and reducing externalities like congestion and traffic fatalities. All of those are critically important and deserve separate conversations, but the lens we’re using here is decarbonization, and from that perspective, their contribution is modest, at least in the Carbon Free Boston model.

The low carbon pathway also includes some very ambitious proposals on road pricing. They’re represented by the blue bar labelled ‘pricing’. The policies proposed would be dramatically more ambitious than anything that currently exists in North America. Just by itself, the $10-$15 dollar cordon charge they include in the model would be unprecedented. But they also include a $5 parking fee and $0.20 per mile VMT fee. All told, they estimate these policies could reduce VMT by 18 percent. That’s not nothing, but given how politically difficult each of those policies is, it’s a sobering number.

Electrifying Cars

Everything proposed so far - one of the most ambitious programs of transit investment and road pricing you could imagine in an American context - would reduce emissions by about 20% from baseline.

That leaves the bulk of the work to electrification. Even if the grid stayed at its current emissions intensity, the electrification of all light- and medium-duty vehicles, including transit, would reduce emissions 29% by 2050. That action alone, without changing the intensity of the grid, lowers emissions more than all of the mode shift and demand limiting measures described above.

But, as many of you know, the grid is slated to get a lot cleaner in the future, thanks in part to ongoing declines in the cost of wind and solar. The Massachusetts Clean Energy Standard requires 80 percent renewable electricity by 2050. Assuming that standard can be met, transportation emissions would decline by a further 32 percent, the biggest single drop in this entire transport plan. Just to repeat that: the grid getting to 80% renewable power is the single biggest contributor to transport decarbonization in the Carbon Free Boston proposal, even though it’s not a transportation policy. It’s an example of how vehicle electrification is a strategy that allows the transportation sector to benefit from the remarkable progress the electric power sector is making in cleaning up its act.

Unfortunately, vehicle electrification is a process that’s mostly out of city control, at least in the US. That’s one reason the authors of the report advocate for Boston to work towards a ‘low emission zone’ modeled on London’s, something US cities don’t have the authority to do, although this newsletter thinks they should.

Cleaning up the Grid

It’s one thing to electrify every vehicle in Boston. But that power has to come from somewhere. How much would all that new electricity consumption add to Boston’s total demand? The report states that “full electrification by 2050 could increase electricity demand by up to 25 percent compared to 2016 City of Boston consumption.” That's a lot of new renewable power, and every extra kilowatt-hour drawn from the grid has to be produced somewhere.

Renewable power projects aren’t without environmental cost or political challenges. Look no further than Massachusetts' own star crossed history with Cape Wind. That’s a good reminder that even if we do manage to electrify everything and make our grid carbon free, ditching cars and driving them less still helps, because renewable power is not a magic ‘get out of jail free’ card. It’s going to be extremely hard to build a 100% renewable electric power grid, and every bit of energy we can save should make that challenge easier. It’s also worth remembering that this model doesn’t account for the ‘life cycle’ emissions of all those cars - the emissions created in their manufacture - which are actually higher (at least today) than for gasoline cars. That’s something to consider, too.

Much like in Toronto, Boston’s plan suggests that electrification is most of the answer to urban transport decarbonization, even in big, dense cities. That runs counter to some of the popular conversation, and it even runs counter to the report’s own branding, where a bicyclist adorns the cover of the transport section despite cycling making up less than 1% of their proposed emissions reductions. I’m curious how you react to that. Do you have other climate action plans that outline different pathways? I’d love to see them.

New & Worth a Read

Some big news last week out of California, where Governor Newsom announced a 2035 ban on new internal combustion engine car sales [link, full text of the executive order]. Just last week, we wrote about 2035 being the latest date you could impose a ban and hope to be net zero by 2050 (maybe he’s reading the newsletter?). More:

Some modeling of the emissions implications of the move.

An audio deep dive.

A description of all the legal obstacles the move will face.

Now California needs to find 25% more renewable electric power.

With the UK reportedly moving their end of new gasoline car sales up to 2030, should California actually have been bolder?

From the world’s fifth largest economy (California), to its second largest: China. China announced its intention to go net zero by 2060 [link]. China had never previously committed to zeroing out its emissions, and while 2060 is a long time away, if the commitment is serious it would entail some real changes in the short term. More:

We should probably wait for the next five year plan to judge.

Actually, working from home increases emissions?

The strange Nikola boom and bust story continues, with its founder stepping down.

If you had to read one thread on US transport decarbonization, this would be it.

Till next time,

Andrew

Really nice to read a commentary based on data rather than skewed by "professional ideology", as so much commentary on urban transportation is these days. As Andrew points out, by far the largest gains projected for the Boston region are the result of performance improvements in technology which also help to induce changes in the actual technologies used by our society. And this is precisely the path of improvement we have seen in the past 50 years in the USA, in which the amount of pollutants per vehicle mile traveled have been reduced by 98-99% with newer vehicles compared to the baseline of 1970. And fuel economy--which is directly related to the amount of carbon produced from vehicles--has been improved by about 50% over this time span. These performance improvements--a direct result of federal government policies with important pushes from the State of California--completely swamp the effects of any other policies or behavioral changes impacting urban transportation outcomes. And while much remains to improve the carbon impacts of the automobile, the fact that we have come so far with this policy theme seems to me to be a very encouraging development. Scenarios that show decarbonization of urban transportation occurring largely as a result of technology improvements (including substitution of the direct energy source of the vehicle) are consistent with what we know has already worked and produced enormous benefits. Scenarios that rely on changes in consumer behavior, including those premised upon political actions that would price travel in ways never implemented in American society previously, seem much less plausible pathways than those that we have seen have produced beneficial results to date and are consistent with how the government has related to its constituents in at least the USA historically.